Two years ago, in 2019, Rwanda, who had effectively been increasing healthcare access in the country for almost two decades, declared full commitment to achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) at the UN General Assembly in New York. That is not news in itself – the 193 member states sign these types of declarations all the time. However, the case of Rwanda is particularly special for two reasons: unlike most neighbouring countries Rwanda is close to achieve its goal of UHC, and it has done so through digitization.

Talking about health and reinforcing national healthcare systems has become topical for obvious reasons, reviving the ongoing debate about how much medical personnel is needed to safeguard a country. The answer is simple: as many as possible. Unlike Rwanda, when looking at the recent past, several African nations have many reasons to be upset about when it comes to investing in their own healthcare systems without obtaining the expected results. This is especially frustrating in a context in which overseas countries are importing African doctors and nurses, through a well-known ongoing outflow of medical personnel to Europe and the United States among others. African Governments spend an average of USD 20,000 to USD 60,000 on training and educating doctors, nurses and medical personnel, not counting the infrastructure needed and R&D initiatives.

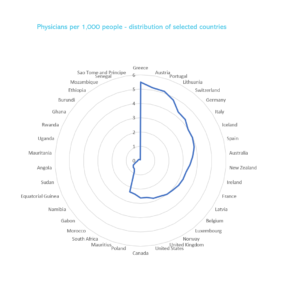

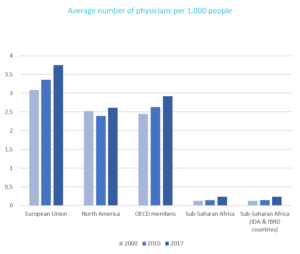

Not oblivious to the struggle lived in the healthcare system of many African nations, the international community has acknowledged that recruiting medical personnel must be balanced and fair, which reflected in the WHO signing of The Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, following Resolution WHA63.16. The practicality and enforcement are still being discussed at the institution, as it relies mostly on ethical principles difficult to measure at times. Nevertheless, there are limited ways of stopping doctors accepting economically attractive offers in less stressful contexts elsewhere. Going to the root of the problem, doctors leave not only because economic conditions may be better, but because they are constantly overwhelmed by numbers of patients. This is normally measured analysing 1000 habitants/doctor and the two graphs below show the difference in doctor-to-patient ratio between Africa and the “North”.

How did Rwanda do it?

How to deal with increasing populations, the urban-rural coverage gap, access inequality due to private healthcare absorbing physicians, and effective policy implementation rather than just pouring money in education are priorities policymakers must deal with now. The problem is only going to keep getting worse. Going back to the case of Rwanda of a coordinated national effort and innovation, we can identify the steps the Government followed to land in its current advantageous position. Prior to launching the famous national Community Based Healthcare Insurance (CBHI), “Mutuelle de Santé” the Government addressed connectivity issues in the country, it doubled up on collecting digital records and identification of its rural population, and opened the door to private-public-partnerships. Although not necessarily in sequence, we identify 7 steps:

- Strategic connectivity penetration increased up to 75% of the population.

- Coordination of healthcare system related software and data storage.

- Roll-out of digital National Identity (NI) recognition over a period.

- Training and implication of public authorities and government representatives toward Universal Healthcare Coverage (UHC), including the series of UNESCO/WHO training meetings that took place between November 2012 and May 2015 in Harare (Zimbabwe), Dakar (Senegal), Maputo (Mozambique), Kigali (Rwanda) and Cairo (Egypt).

- Strategic partnerships with digital healthcare service providers under national sight, highlighting the e-health facilities deployed by UK based company Babylon Health Ltd.

- Information campaign for population usage of new existing digital tools, and access to tailored information.

- Effective reduction of physical inflow of patients now attended digitally for non-emergencies or scheduled treatment.

For at least 4 of these important projects, health technology adaptation is central, and it does not end there. Africa imports most of its medical equipment, with some sources stating that the cost ascends to USD 3.2 billion. Generating an indigenous health-tech industry would be an advancement for local resourcing and cutting cost in the long run. This does not mean fixating on local-only approaches such Local Economic Development (LED), but pragmatically maximising the dual opportunities for the international investment community and for local technology ventures or local-majority-owned partnerships.

The case of Rwanda is essential because it also reflects the groundwork required towards UHC in Africa through digitisation, which has been analysed by previous research which highlight: (a) the poor coordination of mushrooming pilot projects, (b) lack of awareness and knowledge about digital health from policymakers, (c) lack of infrastructure for testing and engineering, (d) poor internet connectivity and (e) lack of interoperability of the numerous digital health systems.

Acting now, for economic reasons too

Reflecting on the urgency of rethinking strategic policymaking to improve healthcare systems in the continent, national governments are aware that the consequences of the present outflow of doctors are damaging their economies in multiple ways, which can be addressed by investing in health-technology:

- The immediate economic loss, resulting from high earners abandoning the economy – not just doctors, but those that rate healthcare as a priority.

- The permanent loss of medical personnel, which has been funded, educated, and trained by the “exporting” country.

- In need, healthcare systems at a loss may require accepting an inflow of more expensive doctors, putting even more pressure on national budgets.

- Transfer of doctors from the public healthcare system to the private sector, or medics combining public and private practice, widens the gap on quality and affordability of the public healthcare system.

- The training structure for medical personnel is becoming severely affected, adding an additional constrain to Government spending in trying to maintain the quality of lecturers and the supply of a younger generation of physicians.

- Lastly, the existing divide between urban and rural medical servicing reach is increasing, and the effects of COVID-19 have been devastating, adding additional pressure to rural medical personnel that constantly falls short on equipment and human resources.

These should be enough reasons to realize that the current strategy of investing in education and training only, combined with conditionality of scholarship post-graduation is not enough. Just like Rwanda did it, with a vast rural population and a smaller GDP, a coordinated health-technology response shows that leapfrogging towards UHC is possible.

Our recommendations

(a) Addressing lack of medical personnel mainly doctors with remote consultations with local and international servicing partners, which pass through e-health points for the wider population if home internet is not available.

(b) Patients lack awareness or uninformed about health issues is already being addressed through digitization of the user, but not enough is being done on enabling adapted health information of easy access, requiring Tech/private – NGO – Government approaches.

(c) Inherited shortage of resources and machinery is endemic and has created a cycle of dependency. Unilateral and multilateral (African Union) technology partnerships based on fairness (Fairtech) and common good would prove successful in the short and long term. Investing in-country resources and suitable digital solutions would translate into cost-saving in the expenditure cycle in overall healthcare.