Electric vehicles (EVs) are gaining traction and attention in Asia-Pacific (APAC), as evident from increased sightings of the Tesla Models Y and 3 and Hyundai Kona Electric in many cities. Yet, despite global electric vehicles crossing the 10 million mark in 2020, the move towards widespread adoption of EVs remains sluggish.

Governments in APAC are focusing on EVs as a potential pathway to decarbonization and autonomous mobility. Thailand is targeting all newly purchased cars to be electric by 2035. This ambition to phase out internal combustion engines (ICE) is similarly reflected across other markets across APAC, including Singapore, China, and Japan.

While these sustainability goals are laudable, the pertinent question lies in whether APAC is primed for mass EV adoption.

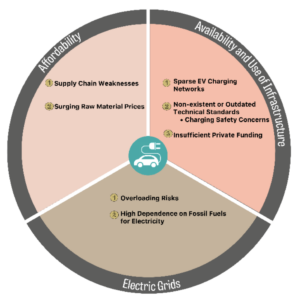

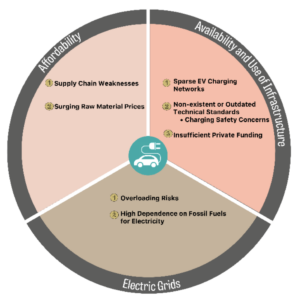

Let us take a look at some of the key policy issues challenging the mass adoption of EVs in APAC:

1. Affordability

EVs’ affordability is primarily determined by two main elements, namely, the production costs for which batteries are a major component, as well as the slow rate at which tariff reductions are effected. To achieve mass adoption, EVs’ pricing needs to be at least on par with ICE vehicles.

The recent wave of price hikes in EVs due to rising production costs indicates a worrying trend for both consumers and manufacturers. In Southeast Asia, the annual cost of owning an EV (including the vehicle cost) is more than that of an ICE vehicle.

The ownership costs of an EV will continue on an upward trajectory as manufacturers grapple with the surging costs of raw materials used in batteries, largely exacerbated by international supply chain disruptions and geopolitical tensions. One-third of an EV cost is attributed to the EV battery pack of approximately USD,7300, which contains key metals such as nickel and lithium. The soaring prices for nickel and lithium, however, have made EV batteries more expensive.

EV manufacturers face additional production costs as governments continue to impose tariffs on imported EVs. India, for instance, has levied a 100% import duty on fully imported EVs with a value of more than USD 40,000. In Thailand, imported EVs are levied with a range of taxes, with the highest at 80% from Europe. Even in other APAC countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines, where governments have recently adopted a zero-tariff regime for imports of EVs under certain conditions, these policies and their ensuing impact on the EV market will take time to be felt.

2. Availability and Use of Charging Infrastructure

In addition to affordability issues, insufficient charging infrastructure within convenient proximity has been identified as one of the main concerns for the switch to EVs in ASEAN markets. Many EV owners face range anxiety – fearing that they will run out of power and be left stranded in the middle of the road – due to the prevalent misconception that EVs have a shorter driving range. As such, many interested EV buyers are held back in their potential purchases due to the shortage of public charging points. The deployment of a widely accessible charging network would help to mitigate range anxiety concerns and hasten EV adoption.

Governments have attempted to close the infrastructure gap, but more can be done. The charging infrastructure entails a certain level of complexity as it is not as simple as repurposing existing gas stations. The longer charging time of an EV, which typically takes at least 30 minutes, entails that chargers will have to be installed in places where people can park their cars for extended periods. In addition, having an updated and harmonized charging standard encompassing technical and safety aspects will provide assurance. In Singapore, the Government has introduced an EV charging standard and moved to expand the EV charging infrastructure to all public car parks.

Beyond the necessary changes to land use planning, the deeper issue lies in the lack of incentives for the private sector to co-finance this massive infrastructure development. Public finance is inadequate in meeting the financing gap for EV charging infrastructure globally, especially in the COVID-19 period where budgets are stretched. According to technology giant Siemens, the global investment gap for EV charging infrastructure by 2024-2026 is estimated to be USD 104 billion. In both developed and developing markets, governments must depend on private capital to develop a comprehensive network that is accessible for EV users. To attract the private sector, APAC governments can look at the EU’s well-developed commercial EV charging incentives in the form of grants and tax relief to help companies install EV charging infrastructure. Thailand has recently moved to expand its tax relief to cover smaller charging stations.

Some governments outside of Asia have already started to engage in public-private partnerships to implement EV stations, albeit at a nascent stage, such as the US and New Zealand. In New Zealand, the government and the private sector co-financed charging infrastructure projects and BEV trucks in 2020, as part of the government’s plans to meet its target of net-zero emissions by 2050. Afterall, private sector solution providers and operators of charging networks play a key role in scaling EV charging infrastructure.

Beyond tackling the shortage of charging networks, governments face additional policy challenges related to the improper use of EV charging stations. “Unplugging other EVs?, Hogging charging lots?” are common complaints by EV drivers. EV-charging etiquette and social norms will soon surface in governments’ development of new guidelines to spur EV adoption.

3. Electric Grids – Sources & Infrastructure Optimization

EVs tap upon power grids to charge their batteries. As electric mobility is projected to grow and more, EVs will be on the roads and existing power grids will be challenged especially when too many EVs concurrently tap into the grid during peak periods. In large countries with remote areas, there is strong imperative for governments to build a well-functioning grid system to deliver energy over long distances. Without proper demand management, the accelerated electrification of road transport could potentially strain state power networks and risk overloading grids. In Southeast Asia, there is an absence of robust power grids to support large-scale electrification, especially in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. With mass adoption, EVs may also be collectively viewed as an external mobile power source supplementing the grid where necessary. Policies should be developed to facilitate these energy exchanges under a certain framework to optimize infrastructure deployment requirements. Governments would need to partner with industry to augment their existing power grids with energy storage infrastructure so as to support the growth of electric mobility.

In a region dependent on fossil fuels for power generation, Asia’s EV market further begs the question of whether EVs are truly cleaner or sustainable. Coal is still a dominant fuel in Southeast Asia’s power market. While EVs are more energy efficient than ICEs, their carbon emissions are tied to the manner in which the electricity powering their mobility is being generated. As governments in Asia race to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2030, they must be prepared to face the broader energy transition challenge of switching from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy for power grids.

Figure 1: Key Challenges for Mass Adoption

Comprehensive policy framework is fundamental to mass adoption

EVs represent the next revolution in mobility. EVs also promise to bring about potential sustainability outcomes while delivering economic spinoffs. Consumers’ growing attention to EVs supports its mass adoption potential, but this can only be realized through a comprehensive suite of policies addressing issues related to affordability, availability, and the use of charging infrastructure, as well as electric grids. While recognizing the differing timeframes of these three critical policy components, it is important to note that the mass adoption of EVs can only happen when all three of them have been adequately addressed through public-private engagement and partnerships.

Subscribe to our news alerts here.