In past editions of Access Partnership’s Sustainability Conversations series[1], we have provided an overview of the nature-positive economy and latest updates from major international reports and events, including IPCC AR6 III and the World Economic Forum’s 2022 Davos Summit. In this edition, we explore the importance of externality pricing models and their relevance to the nature-positive economy.

The global economy cannot value what it does not price

Our past research with the World Economic Forum indicates that developing a nature-positive economy could unlock US$10.1 trillion of annual incremental business opportunities and 395 million jobs globally by 2030. 59 business opportunities associated with 15 major socioeconomic transitions will deliver this value, ranging from regenerative agriculture to using nature as infrastructure, from circular models of production to a nature-positive energy transition.

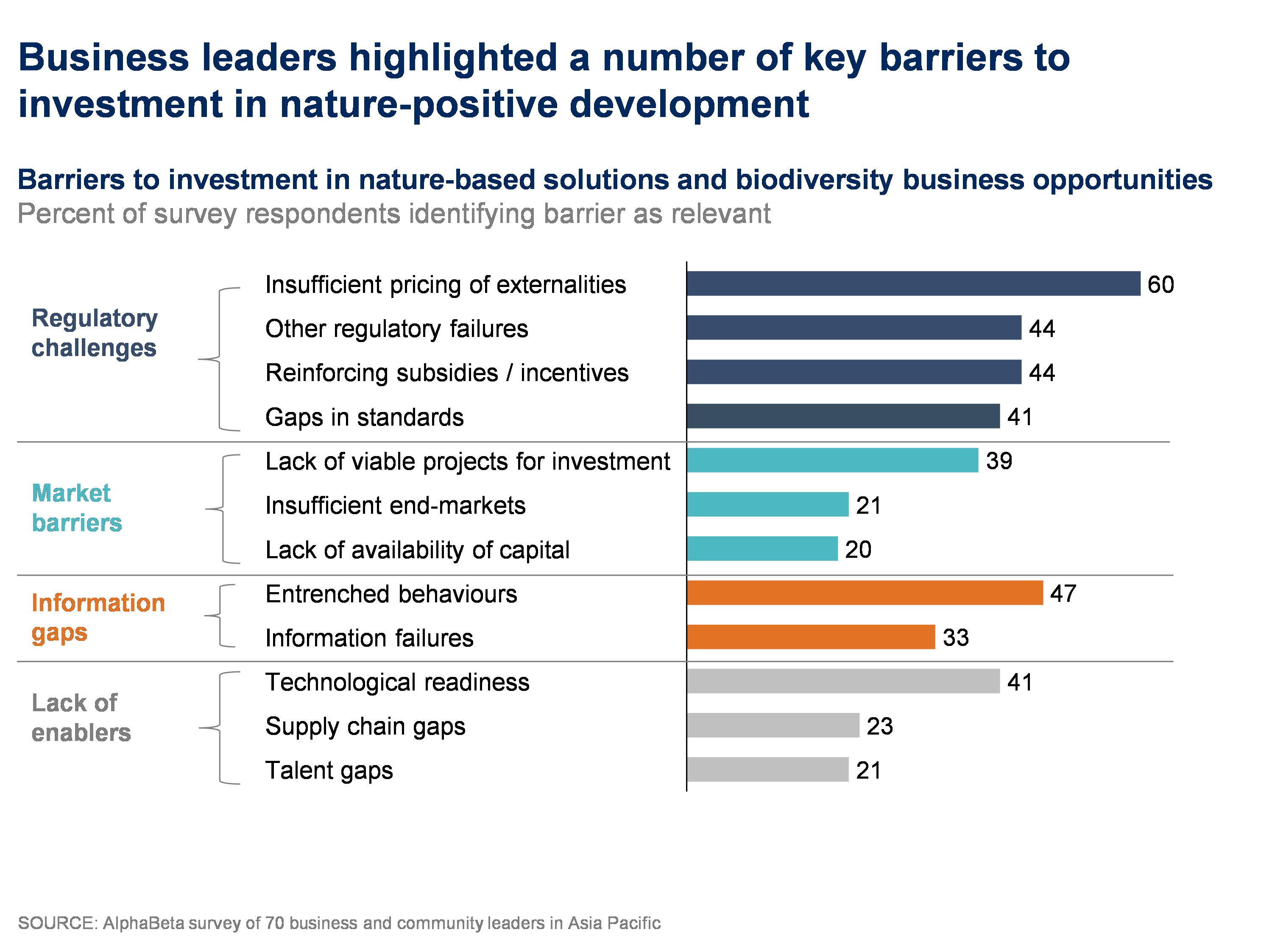

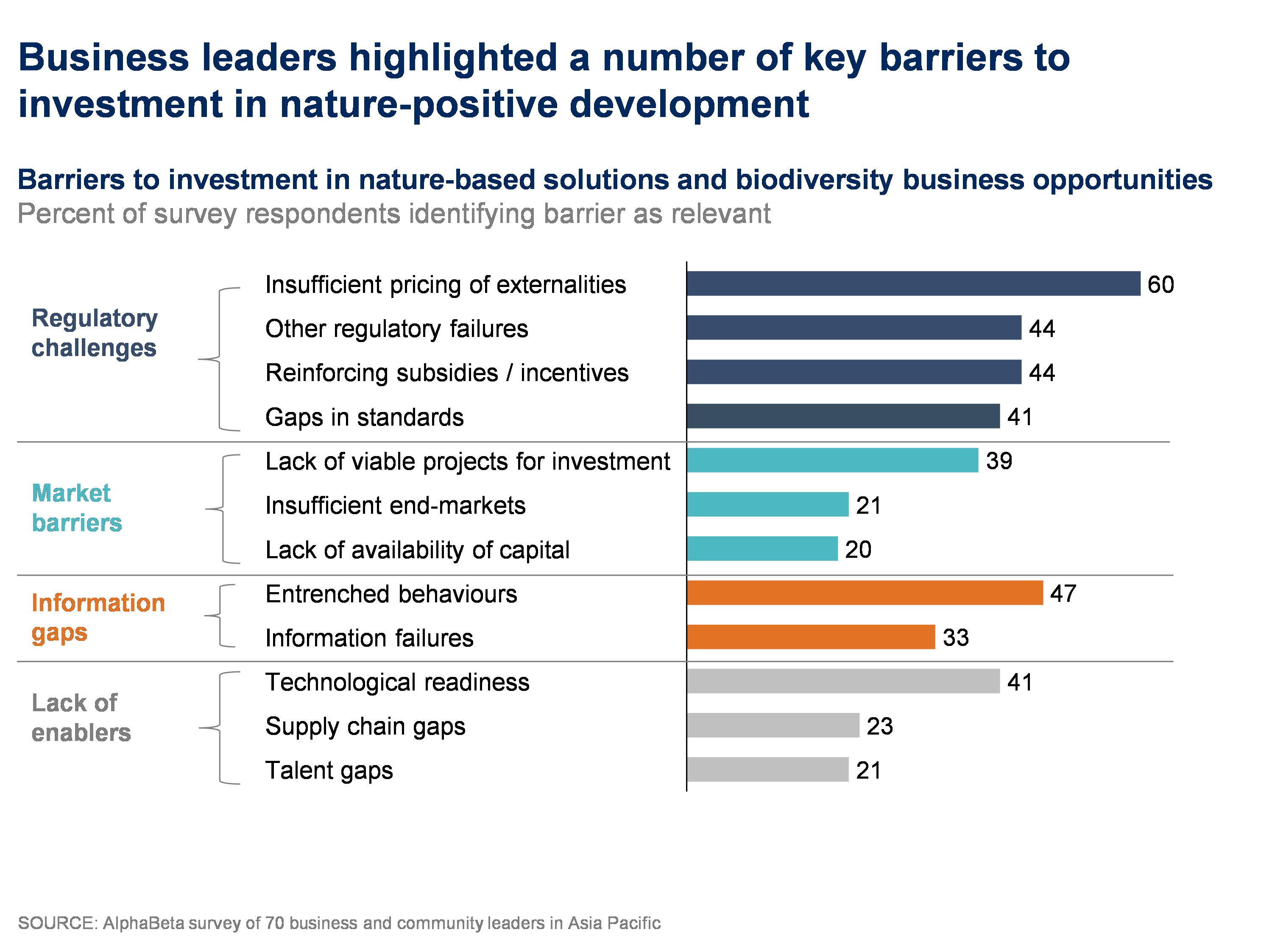

Despite the large opportunities presented by nature-positive business models, many challenges remain in mobilising the requisite financial capital to develop these models and unlock their economic value. In an exclusive survey we conducted in 2021 together with Temasek and the World Economic Forum, business and community leaders in the Asia Pacific region highlighted a range of key barriers to investment today (Exhibit 1).[2] The barriers identified, while interlinked, can be broadly categorised into four areas.

Exhibit 1

Principal among the key barriers to investment is insufficient pricing of externalities in goods and services, with 60% of surveyed business leaders indicating this as an important barrier to investment. Environmental externalities are the negative consequences on nature and biodiversity that result from human activity. Insufficient pricing of externalities for products and services disguises their true cost and environmental impact, particularly in terms of GHG emissions. Many forms of natural capital are in fact available at no charge, which artificially lowers the cost of nature-negative business models.[i] The cost of such externalities can be extremely high – it was estimated that the global value of environmental externalities in 2013 was US$4.7 trillion across just water use, GHG emissions, waste, air pollution, land and water pollution, and land use, or 7% of global GDP in that year.[ii] All externalities accounted for US$7.3 trillion – or over 10% of global GDP.

Why externalities remain unpriced in our current economic system and what it means

The reality is that our global economy has always prioritized economic cost efficiency, favouring ‘quick wins’ that solve short-term problems but limited long-term consideration of public welfare. Urban planning and project design provides a good example. Few city governments in low- and middle-income countries have the power, resources or trained staff to provide their burgeoning populations with the adequate utilities, services and facilities needed for integrated urban living.[5] Much consideration is given to the structural integrity of built structures and land-use or zoning regulations, therefore solutions for common urban problems such as water supply, transport or power are often considered in an isolated/centralized manner, usually favouring grey infrastructure. This means that other complex and interacting variables in the surrounding environment are not always accounted for, such as land rights, disruptions to ecosystem services and impacts on the rural hinterland, which cities often attempt to encroach upon.

Many fiscal policies also make destroying nature cheaper than protecting or leveraging it. In particular, subsidies and tax reliefs for land, fossil fuels, road transport and water artificially lower the costs of nature-negative business models in these areas, and far outnumber existing incentives to protect nature.[6],[7] Many expected the COVID-19 pandemic to be a turn-around opportunity, but according to the Greenness for Stimulus Index the measures announced in response to the pandemic are predicted to have a net-negative environmental impact in the US, Russia, Mexico and all countries analysed in Asia Pacific, including China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan and South Korea.[8]

Insufficient accounting of environmental externalities in today’s economic indicators and regulatory models therefore distort economic decision-making. Without the externalities being factored into the prices of products and services, nature-positive business models that reduce or eliminate environmental externalities at potentially higher initial costs of input materials, technology, production equipment, and/or labour may be less attractive investment opportunities in contrast with business-as-usual, nature-negative production models. Our past research with the Business and Sustainable Development Commission (BSDC) indicated that, for many business opportunities associated with the SDGs, repricing opportunities by removing subsidies and properly pricing resources could increase their value by almost 40%.[9]

The business community has issued a strong call for externality pricing

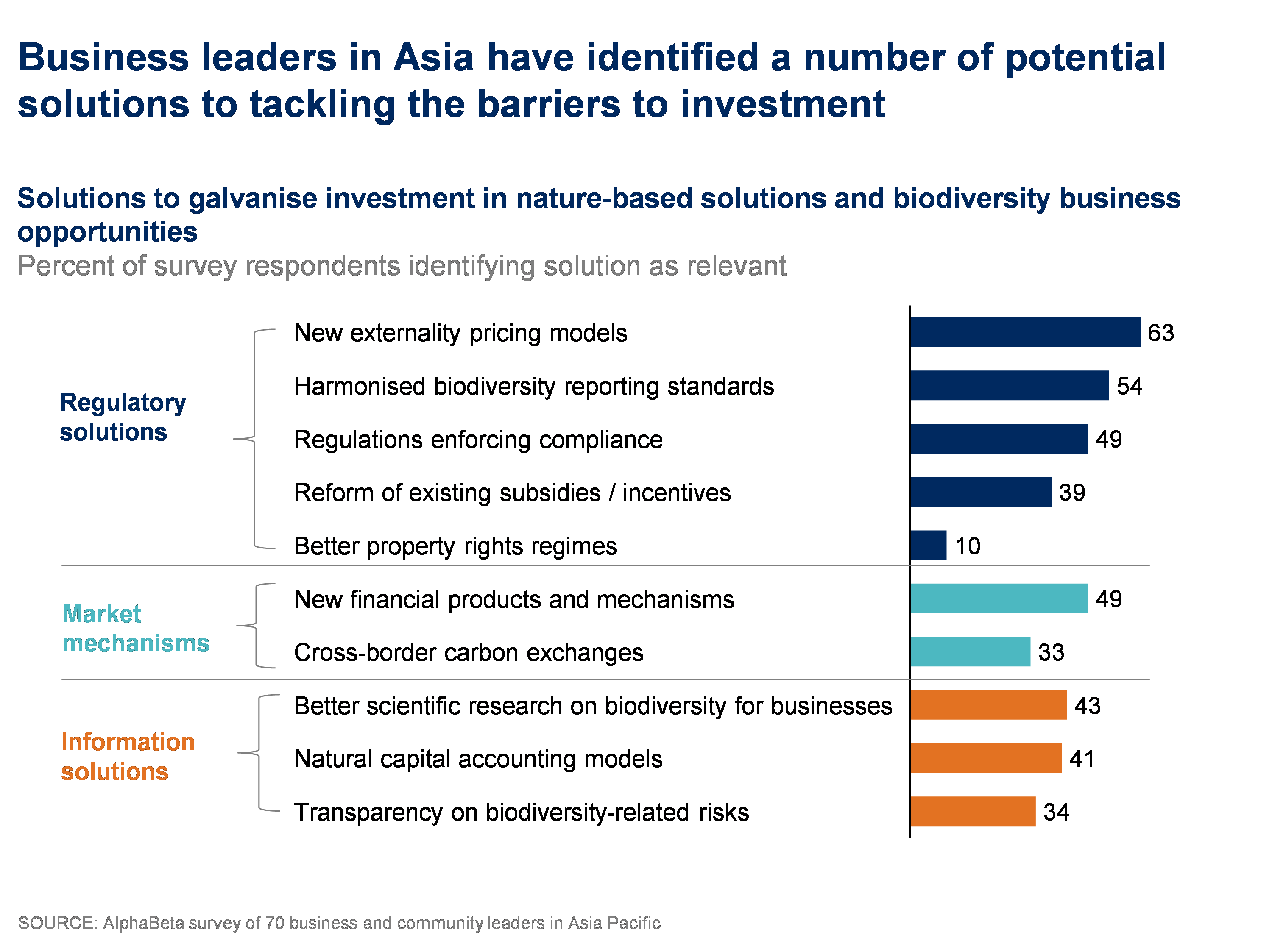

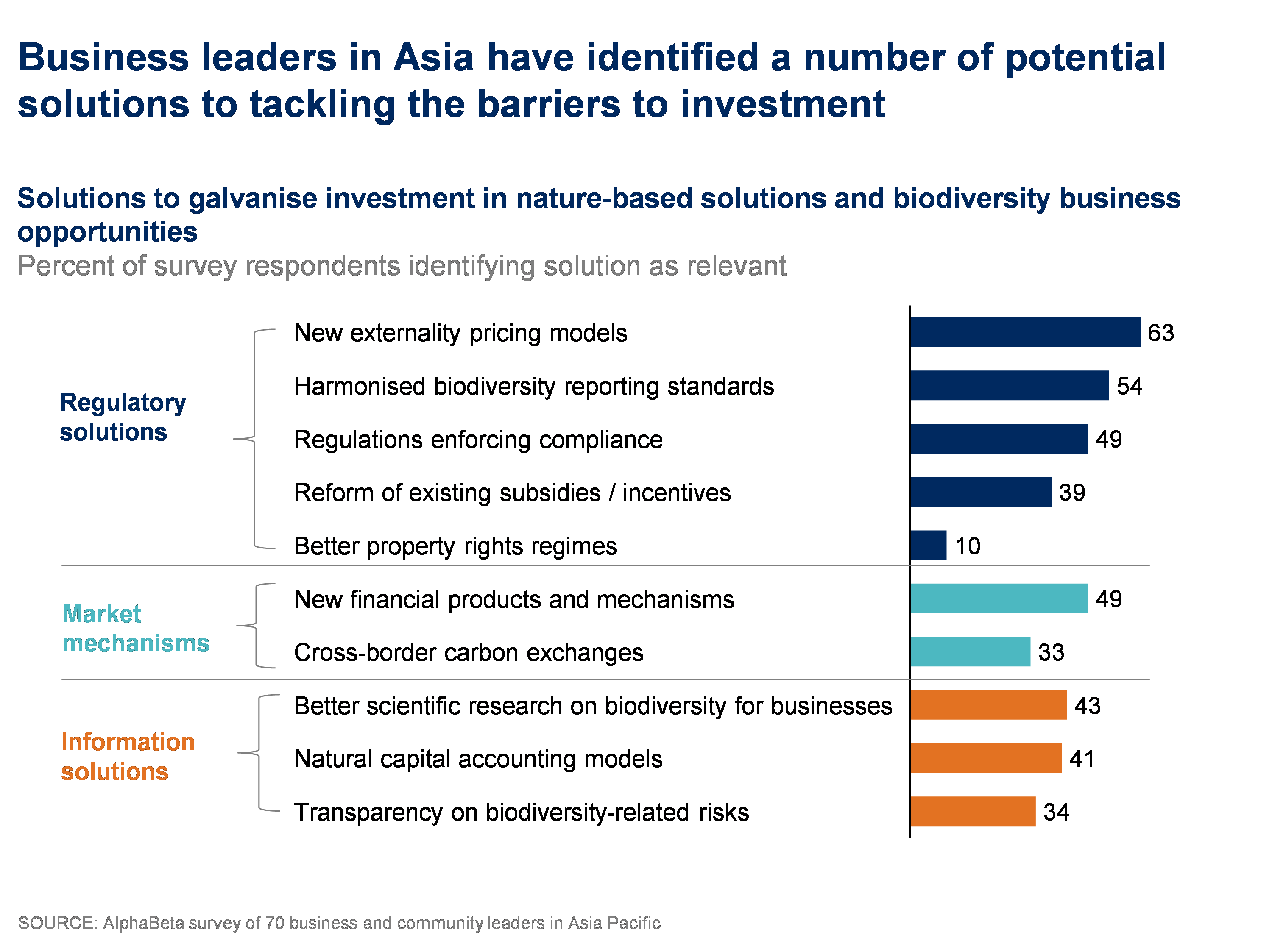

In the same survey, business and community leaders in Asia Pacific identified a range of solutions to address the key barriers to investment today to unlock the financing required over the coming decade for a nature-positive economy. These solutions can similarly be categorised into three broader areas – regulatory solutions, market mechanisms, and information solutions (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

63% of surveyed respondents agreed that externality pricing models are a key solution – the highest of any highlighted in this survey. Such models would be designed to capture the true cost of natural capital and environmental externalities. Some progress has been made in recent years on factoring in externalities, with carbon pricing being the most extensively studied and implemented. Evidence has shown an impact in the form of reduced emissions. In Asia, Japan was the first country to implement a carbon tax in 2012.[10] Statistics from the National Institute for Environment Studies in Japan report a decrease in emissions by 12% in 2018 compared to 2013 levels, which was attributed to the use of low-carbon electricity incentivised by the carbon tax.[11] In the United Kingdom, a hike in carbon taxes from EUR7 per tonne to EUR36 per tonne over 2012 to 2018 led to a fall in electricity-related emissions by 73% over the same period. [12] It is estimated that for every EUR1 increase in carbon taxes, emissions from fossil fuel consumption could reduce by 0.73% over time.[13]

However, beyond carbon pricing, there have been significant challenges in pricing in externalities such as water, energy, and natural resources. These challenges are largely due to large variances in the abundance of natural capital in different regions, difficulties in ascertaining the relative importance of ecosystem services to production in specific locations, measurement challenges in determining biodiversity impact, and related difficulties in creating an understandable pricing regime. The latest research still largely discusses externality pricing at a theoretical level.

The implementation of externality pricing models may also bring about its own challenges. A lack of easily available and trusted data for decision-makers impedes the inclusion of externalities in decision-making. Another risk is that increased costs may simply be passed on to consumers. Analysis by Trucost and McKinsey shows that if the environmental impact of production of food was included, the prices of soft commodities could increase by 50 to 450%.[14] This could bring about disproportionate impact on low-income consumers. For instance, carbon emissions tax leading to increased cost of utilities would impact poor households more, as they spend a greater proportion of their incomes on utilities compared to higher-income households.[15] The impact on competitive dynamics in the food and agriculture system of subsidy reform and/ or carbon pricing in particular could also be dramatic.

Where governments and business can begin action

Natural capital accounting models are an important information tool which could begin to plug this gap. Such models aim to provide businesses and governments with a systematic way to measure natural capital usage, which will both enable externality pricing as well as allow businesses to develop their own pathways to tackling their biodiversity impact.[16] Appropriately accounting for the value of natural capital will be essential for better economic and financial decision-making. As discussed earlier, today’s financial models assume no costs of natural capital despite nature and economic growth being deeply interlinked, which incentivises environmentally damaging business models. There is increasing effort towards the development of natural capital accounting frameworks. The System of Environmental Economic Accounting’s (SEEA) ecosystem accounts are now an international statistical standard adopted by the UN Statistical Commission.[17] The Natural Capital Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services (NCAVES) initiative – set up by the UN, the EU and five other countries, including China and India – is advancing ecosystem accounting. Harmonization of cities’ accounting standards for natural capital, as well as natural capital accounts in macroeconomic surveillance undertaken by international financial institutions, could provide a significant boost for a global movement that strengthens science-based targets for nature in urban areas and embeds nature-related considerations in urban planning. Countries are beginning to incorporate natural capital and ecosystem services into economic measures of success: China’s Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) and New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework are just two examples. China’s GEP program has been piloted in three provinces with plans for broader rollout to support eco-compensation investments.[18]

However, these are still early days for natural capital accounts. Increased investment in physical accounts and ecosystem valuation is needed. International cooperation and the sharing of data will help to improve decision-making around the world. Harmonisation of national accounts should be coupled with technical assistance. Incorporating natural capital accounts in macroeconomic surveillance undertaken by international financial institutions, for example through the International Monetary Fund’s Article IV surveillance activities, would also send a strong signal, inspiring government, and private sector reform agendas to reflect the scale and urgency of the challenge our societies face.

Business leaders have placed great value on scientific tools that help account for environmental impact and resource usage as a significant step forward in the lead up to a comprehensive system for pricing externalities. Such tools have proven helpful particularly in actions towards emissions mitigation. For instance, more than 3,000 businesses are working with the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) to reduce their emissions in line with climate science, with hundreds more developing such targets.[19] Science Based Targets for Nature (SBTN) are an important step in providing companies a similar framework to align their efforts with global nature-related sustainability pathways as part of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.[20] Targets will be linked to the area and integrity of ecosystems, species risk and abundance, and maintenance or enhancement of nature’s contributions to people, with frameworks already in place for businesses to assess, interpret and prioritise, measure, set and disclose, act, and track their strategies for addressing environmental issues.

Interested in externality pricing? Contact Shivin Kohli for this and more on our work in sustainability advisory.

Endnotes

[i] Business and Sustainable Development Commission [BSDC], 2017, Valuing the SDG Prize: Unlocking Business Opportunities to Accelerate Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws-bsdc/Valuing-the-SDG-Prize.pdf

[ii] TEEB for Business Coalition, 2013, Natural Capital at Risk: The Top 100 Externalities of Business, https://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/natural_capital_at_risk_the_top_100_externalities_of_business_Trucost.pdf

[1][1] Access Partnership (2022), “Sustainability Conversations”. Available at: https://accesspartnership.com/?s=sustainability+conversations&post=post

[2] Temasek, WEF, and AlphaBeta (2021), New Nature Economy: Asia’s Next Wave. Available at: https://accesspartnership.com/asias-next-wave/

[3] Business and Sustainable Development Commission [BSDC], 2017, Valuing the SDG Prize: Unlocking Business Opportunities to Accelerate Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws-bsdc/Valuing-the-SDG-Prize.pdf

[4] TEEB for Business Coalition, 2013, Natural Capital at Risk: The Top 100 Externalities of Business, https://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/natural_capital_at_risk_the_top_100_externalities_of_business_Trucost.pdf

[5] Rastandeh, A. and Jarchow, M., 2020, “Urbanization and biodiversity loss in the post-COVID-19 era: complex challenges and possible solutions”, Cities and Health, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23748834.2020.1788322

[6] UNCBD, 2021, “Economics, Trade and Incentive Measures: Perverse incentives and their removal or mitigation”, https://www.cbd.int/incentives/perverse-info.shtml

[7] Li, J. and Wei, Z., 2020, “Fiscal Incentives and Sustainable Urbanization: Evidence from China”, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/1/103

[8] Finance for Biodiversity Initiative, 2021, Greenness of Stimulus Index, https://www.vivideconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Green-Stimulus-Index-6th-Edition_final-report.pdf

[9] Business and Sustainable Development Commission and AlphaBeta (2017), Valuing the SDG Prize. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws-bsdc/Valuing-the-SDG-Prize.pdf

[10] IHS Markit, 2021, “Carbon tax could be key to Asia’s energy transition, GHG reductions: IMF”, https://ihsmarkit.com/research-analysis/carbon-tax-could-be-key-to-asias-energy-transition-ghgeducti.html/

[11] National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan, 2018, Japan’s National Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Fiscal Year 2018 (Final Figures), https://www.nies.go.jp/whatsnew/20200414/20200414-e.html

[12] OECD, 2021, Effective Carbon Rates 2021, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/effective-carbon-rates-2021-brochure.pdf

[13] Sen, S., & Vollebergh, H, 2018, The effectiveness of taxing the carbon content of energy consumption. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 92, 74-99, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0095069616301759

[14] McKinsey Global Institute, 2011, “Resource Revolution: Meeting the World’s Energy, Materials, Food and Water Needs”, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/sustainability/our%20insights/resource%20revolution/mgi_resource_revolution_full_report.pdf

[15] Dasgupta, P., 2021, The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta review, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/962785/The_Economics_of_Biodiversity_The_Dasgupta_Review_Full_Report.pdf

[16] System of Environmental Economic Accounting, no date, “What is natural capital accounting”, https://seea.un.org/content/frequently-asked-questions#What%20is%20natural%20capital%20accounting?

[17] System of Environmental Economic Accounting, no date, “Natural Capital Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services Project”, https://seea.un.org/home/Natural-Capital-Accounting-Project

[18] Development Asia, 2018, “How to Mainstream Natural Capital Accounting”, https://development.asia/summary/how-mainstream-natural-capital-accounting

[19] Science Based Targets, no date, “How it Works”, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/how-it-works

[20] Science Based Targets Network, 2020, Science-Based Targets for Nature: Initial Guidance for Business, https://sciencebasedtargetsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Science-Based-Targets-for-Nature-Initial-Guidance-for-Business.pdf