Dr Samantha Torrance

Leadership, Public Sector

Ethan Mudavanhu

Data Governance

From 26 February to 1 March 2024, Member States gathered at the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13) in Abu Dhabi. Stakeholders have come to expect little progress from the WTO, and the conference failed to achieve many of its primary objectives. However, delegates in Abu Dhabi agreed a last-minute deal to extend the long-standing moratorium on electronic transmissions for another two years.[1]

A group of emerging economy countries had resisted a quick decision on extending the moratorium, re-examining the costs and benefits of the measure. The tech sector will feel relief at the resolution. However, with attention firmly on the decision itself, questions remain over what may come next. Important developments are now expected on the African continent, while the episode also sends concerning signals for the digital governance landscape that could pave the way for internet fragmentation.

The WTO’s moratorium on electronic transmissions is an agreement among WTO member countries not to impose customs duties on electronic transmissions.[2] The moratorium was first adopted in 1998 and has been periodically extended at subsequent WTO Ministerial Conferences. The primary rationale behind this moratorium is to encourage the free flow of information and digital products across borders.

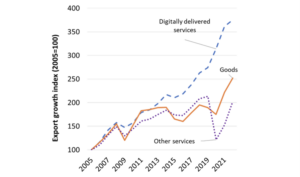

While many will see the decision from WTO as a preservation of the status quo, it has significant macroeconomic implications. An increasing number of goods and services today have a software or digital component, which means the moratorium impacts more trade with each passing year. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the value of global trade in digitally delivered services reached USD 3.82 trillion in 2022, representing 54% of total global services trade and an average annual growth rate of 8.1%. This surpasses the growth rates of both goods and other services.

Put into perspective, the moratorium means revenue: potential tax revenue lost for some; knowledge and operational revenue gained for others.

The proposal to extend the moratorium and its scope was led by the EU and Australia with support from the US and 15 other Member States.[3] The argument put forward was that industries are increasingly more global and digitally dependent and allowing the moratorium to expire would endanger digital commerce, which would have negative repercussions for businesses in every sector.

Additionally, the manufacturing and services sectors’ supply chains require the moratorium to continue to remain resilient. To operate their supply chains and facilitate the manufacture of vital products, the industry relies on an uninterrupted stream of research, design, and process data and software – which the moratorium aids in providing access to.

Opposing this was South Africa, with the support of India, Türkiye, Argentina, and Indonesia. They expressed concerns about its potential costs and implications. South Africa particularly challenged the proposal’s ambiguity, questioning whether the moratorium applies to content or carrier mediums and whether it limits countries’ ability to impose taxes beyond customs duties, potentially conflicting with other WTO commitments.

At the core of their argument, these countries opined that the moratorium disproportionately impacts net importers (which make up most of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs)). By extending it, LDCs argue that they will lose revenue-generating opportunities through duties. As LDCs already have limited options for taxation, they see an end to the moratorium as an opportunity to increase government revenue, which has now been lost for at least another two years. One concession granted to the group in the decision was an agreement to examine the moratorium’s scope, definition, and impact.

An African Agenda

It is worth noting that a draft version of the African Continental Free Trade Area’s (AfCFTA) Digital Trade Protocol was recently leaked. One of the defining provisions of the draft protocol calls upon State Parties to not impose customs duties on digital products transmitted electronically while respecting provisions on Rules of Origin. Therefore, consistent with South Africa’s Foreign Policy in recent years, the wider objective in disbanding the WTO’s moratorium may be to prioritise regional integration and inter-trading instead.

Globally, the US and China dominate the global technology sector and are thus significant beneficiaries of the WTO moratorium. In Africa, however, South Africa boasts one of the most highly advanced domestic tech sectors and can stand to utilise this to its advantage in a regional setting.

A multilateral system failing to keep pace

Zooming out from the African perspective to the global picture, the political capital expended to prevent backsliding is emblematic of a digital governance landscape at a standstill. Wrangling over the moratorium is not new, but this year it has come against a backdrop of slowing progress and backtracking that is paving the way for a more fragmented digital landscape.

In trade, the US last year dropped support in the WTO for text that protects the free flow of data across borders. Although the reasoning behind this change is debated, the outcome is that the e-commerce agenda at the WTO looks less ambitious than it did five years ago. Compounding this image, the US representative demonstrated apathy towards the agenda by choosing to leave negotiations in Abu Dhabi before an agreement was reached.[4] Progress towards a Joint Statement Initiative on E-Commerce has also been slow, with some in the multilateral community objecting to the use of agreements made among a subset of WTO members.

In the wider multilateral system, The UN Secretary-General will host the Summit for the Future later this year, where ambitions for a Global Digital Compact had promised to update institutions to better address modern digital challenges. However, enthusiasm among UN members appears to be waning. There have been no recent mentions of a new ‘Digital Cooperation Forum’, which had previously been suggested by the Secretary-General. Instead of a new mechanism to re-energise the digital governance landscape, it looks as though states will opt to retain the Internet Governance Forum as the only major multilateral event for digital governance.

Elsewhere, the UN Tech Envoy has become less bullish about innovative new measures to govern AI at the global level. An interim report from the Secretary General’s High-Level Advisory Body on AI, which is being coordinated by the Tech Envoy, had indicated that it would propose new global institutions to rise to the challenges and opportunities posed by developments in AI. However, The Tech Envoy made statements at the World Government Summit and UNESCO’s AI Ethics conference last month that rowed back from this rhetoric. Instead, the line is now that the Body will not necessarily suggest new arrangements.

There is a real possibility that these major initiatives opt to tinker with existing multilateral frameworks and that no new bodies or institutions are developed. This will leave a vacuum likely to be filled by numerous regional or national initiatives, confusing an already fragmented landscape. If this is the case come December 2024, it will be difficult to claim that the digital global governance system has kept pace with the technologies that concern it. All of this means that the global landscape becomes increasingly unpredictable.

This is not quite the end of the debate. Sights will soon be fixed on the WSIS+20 review in 2025. For those with a stake in digital governance, this is the final key moment where the landscape could be fundamentally reshaped.

Access Partnership has the global network and expertise to help you navigate the global policy environment – be those developments in Africa or the multilateral system. If you are interested in identifying risk and opportunity in this fast-moving sector, please contact Samantha Torrance at [email protected], Ethan Mudavanhu at [email protected], and Declan Shaw at [email protected].